Alison Fong is a senior Honors College student majoring in history, international and global studies, and Asian studies. Currently, she is the University of Arkansas Museum’s social media and outreach intern. After college, Alison desires to pursue a masters in applied & public history and further her knowledge of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Special thanks to the University of Arkansas Libraries and to Special Collections for providing access and information to pictures and records that have aided in the making of this blog post.

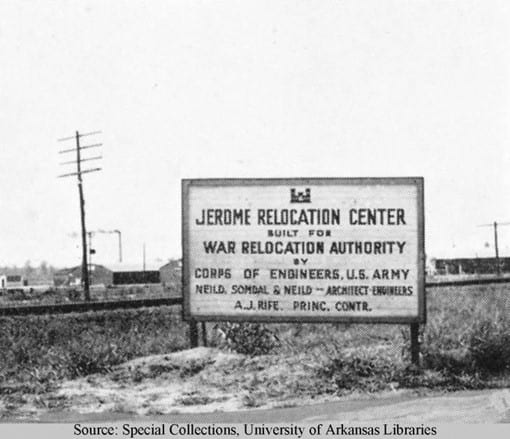

Figure 1 Construction sign at the Jerome Relocation Center, which housed Japanese Americans during World War II.

Beginning February 19, 1942, around 120,313 Japanese Americans were relocated from their homes into internment camps that populated the Western, Midwestern, and Southern states of the United States as a result of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s authorization of Executive Order 9066. At the time, the forced relocation was a response to the belief in the security risk that Japanese Americans posed after Imperial Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. However, this decision is now viewed as a product of racism and discrimination, and marks one of the many dark times in American history.

In Arkansas, two internment camps were constructed to house the internees: one in Rohwer and one in Jerome. Rohwer and Jerome were the last two camps to be opened with the first camp in Manzanar, California having opened in March 1942. Rohwer officially opened its doors in September 1942, while Jerome, the smallest of the ten facilities, opened in October 1942 in Denson, Arkansas. Both Rohwer and Jerome at their peak housed approximately 8,500 incarcerated Japanese Americans each.

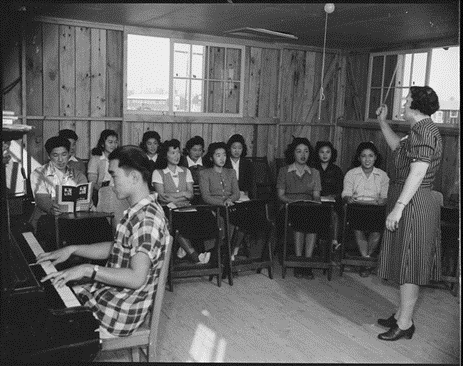

Figure 2 Rohwer Relocation Center, McGehee, Arkansas. A Music class and vocal lessons are taught by Miss Leola Parsley.

When we see photographs of Rohwer and the daily lives of its inhabitants, we are led to believe that the families and individuals living in Rohwer led peaceful lives in their time at the camp. There are photographs of gatherings and parties, classes that uphold traditional Japanese crafts, smiling school children performing the founding of the United States, and high school yearbooks featuring an eclectic mix of classes, clubs, and committees. For the most part, life in Rohwer seemed normal on the surface, and these photographs are almost enough to blind us to the true tension and turmoil that bubbled amongst the incarcerated.

In contrast to Rohwer, the incarcerated at Jerome experienced a far different experience of internment. Indeed, the same activities took place in Jerome as they did in Rohwer, such as arts and craft classes, resourceful social and culture clubs, and sports events. However, life in Jerome was difficult for many other reasons. Out of the ten facilities, Jerome was the smallest and was quite overcrowded. The barracks was poorly insulated and cramped, and several families had to be packed into one-room “apartments”. The other camps also experienced poor living conditions and strict supervision by armed guards, but Jerome’s living spaces, mixed with the moist and humid conditions of the Arkansas Delta, led to the spread of malaria, typhoid fever, and influenza.

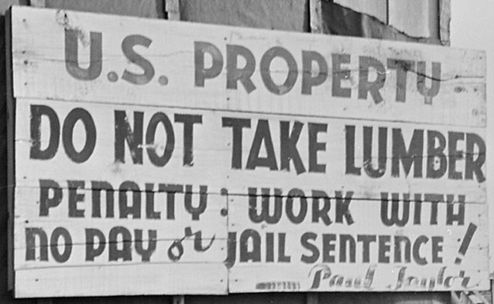

Jerome’s camp director, Paul A. Taylor, insisted on the self-sufficient maintenance of the camp by employing the internees to chop wood from the surrounding forest to produce energy and heat instead of requesting coal. The task was dangerous and arduous, and workers felt exploited and underappreciated due to the lack of safety measures and the lack of food. The WRA were conscious of not “coddling” the incarcerated, so they spent 37 cents on meals per person, which was lower than the allotted amount for American soldiers at 45 cents, and internees who worked with the WRA on camp operation were intentionally paid lower wages than soldiers and the white WRA staff. Furthermore, Jerome was the only facility that involved shootings of internees by civilians.

Figure 3 Old sign at the Jerome Center’s lumber yard.

While out on a work detail in the woods, three Japanese American workers were shot at by a local farmer, who believed that they were trying to escape. Despite the presence of a white supervisor, the farmer claimed that he thought the supervisor was aiding in their escape. Two out of the three workers were wounded from the incident. This incident, along with the inadequate compensation for their work, prompted workers to go on strike multiple times from November 1942 to October 1943. Eventually, Taylor resigned from his position after a vehicle overturned, injuring 37 workers and killing 1 man.

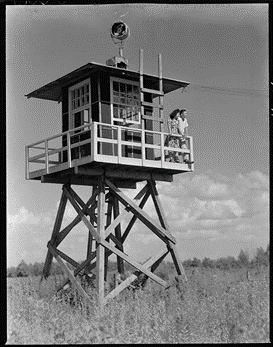

The bouts of resistance and unrest bred even more conflict between the internees and the Arkansas government. Rumors and exaggerated news were leaked to the general public, causing many to believe that Jerome’s internees were lazy and destructive. One report claimed that Jerome’s workers were sabotaging their equipment and refusing to work. As a result, many bills that sought to prevent people of Japanese and Asian ancestry from owning land, working, and attending state colleges in Arkansas were raised in the Arkansas General Assembly. Governor Homer Adkins, a former Ku Klux Klan member, was a major advocate for such legislation. Adkins was initially against the construction of Rohwer and Jerome, but he agreed when WRA Director Milton Eisenhower ensured that the incarcerated would be supervised by white armed guards and removed from Arkansas at the end of the war.

Figure 4 Clara Hasegawa and Tad Mijake take a last look at the Jerome Center from one of the camp’s guard towers before their move to Rohwer.

Eventually, things changed once the WRA issued the “loyalty questionnaire” to all camps. The goal of the “loyalty questionnaire” was to single out “disloyal” internees for transfer to Tule Lake, a maximum-security detention center. Jerome’s adult population were dissatisfied with the “loyalty questionnaire” mainly due to the last two questions. The first asked if the men were willing to serve in the US military, and the second questioned their allegiance to Imperial Japan when most respondents were citizens, US born, and held no allegiance to Japan. Male internees at Rohwer and Jerome felt more pressure to enlist in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which consisted of second-generation Japanese Americans only, due to their proximity to its training facility, Camp Shelby. Those who answered “yes” to the first question, largely out of fear of being labeled as “disloyal”, were enlisted into the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Tensions were already high due to earlier disputes with the WRA, and these tensions were soon directed at their own. Inmates began to grow suspicious of their neighbors and relatives, and some saw others as collaborators, leading to violent in-fighting. Many worried that a negative response to the second question would suggest previous “disloyalty”. As a result, Jerome’s inmates overwhelmingly responded negatively to the second question in comparison to other camps. Nevertheless, about ¼ of the population in Jerome were transferred to Tule Lake “Segregation Center”, which only held internees that were under suspicion or had shown evidence of disloyalty. Conditions at Tule Lake were far worse than the conditions at any other camp, prompting questions of human rights violations.

Figure 5 A truck of Jerome residents waiting for their train that will transfer them to Gila River Center.

With a majority of the camp’s population transferred, the rest of Jerome’s inhabitants were then transferred to other camps such as Granada, Gila River, and the majority going to the nearby Rohwer. On June 30th, 1944, Jerome shut its doors officially and transformed into a German prisoner of war camp for the rest of the war. However, the rest of the nine internment camps would continue until the end of the war with Tule Lake being the last to shut down in March of 1946.

What remains physically of Jerome is a granite monument on the side of a highway amidst farmland and flat fields of grass. What we have left to memorialize this time in history are photographs, documents, art, and oral histories from the survivors. Therefore, on this day we must remember the struggles of the 120,313 Japanese Americans who were subjected to racist abuse and discrimination.

References

- War Relocation Authority. The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Study. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, War Relocation Authority Documents Collection, 1946. https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-282-5/

- Burton, J. F., et.al. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites. Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 2000. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/index.htm.

- Brian Niiya. “Jerome,” Densho Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Jerome.

- Jerome Relocation Center. http://www.javadc.org/jerome_relocation_center.htm.

Image Credits

- Denson High School 1943 yearbook. Jerome Relocation Center Sign. University of Arkansas Libraries Special Collections.

- Parker, Tom. A Music Class in Rohwer Relocation Center. Wikimedia Commons.

- Iwasaki, Hikaru. Sign at the Jerome Center Lumber Yard. Wikimedia Commons.

- Mace, Charles E. Couple Looks At Jerome Center from Guard Tower. Wikimedia Commons.

- Mace, Charles E. Jerome Residents Waitings For Train to Gila River Center. Wikimedia Commons.

Other Resources

- Rising Above: Rohwer Reconstructed: https://risingabove.cast.uark.edu/archive

- National Japanese American Historical Society Digital Archives: https://njahs.org/confinementsites/

- Land of (Unequal) Opportunity: Documenting the Civil Rights Struggle in Arkansas: https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/Civilrights

- Japanese American Internment Archives in Special Collections: https://uark.libguides.com/JapaneseAmericanInternment

- Prisoners at Home: Everyday Life in Japanese Internment Camps: https://dp.la/exhibitions/japanese-internment

- Rohwer Heritage Site: https://rohwer.astate.edu/