Last June, we featured a student’s project produced for Assistant Professor of Classics and Art History Rhodora Vennarucci’s Roman Art and Archeology course. The student, Cheri Ottaviano, reproduced a Roman banqueting tessera held within the Museum’s collections. This June, we are highlighting three new student projects resulting from Dr. Vennarucci’s spring 2021 Greek Art and Archeology class! The students include Elysa Barsotti, Kate Hodgson, and Brynne Moore.

Each student had a chance to study the U of A Museum’s ancient Greek collection hands-on and in-person. Each project focuses on objects of their choice and explores object conservation, gender identity, and ceramic processes.

The Museum maintains files for research publications featuring collection materials. If you are interested in reading Barsotti’s or Moore’s original papers in full, please reach out to Museum staff for access. Hodgson’s exhibition is freely accessible to the public online here.

Care and Conservation of a Greek Lekythos

Elysa Barsotti

Due to limited time and resources, museum professionals most often focus on providing a stable environment and enclosure for an object to be displayed or stored. Conservation, on the other hand, delves deeper and explores more active methods of repairing and stabilizing objects.

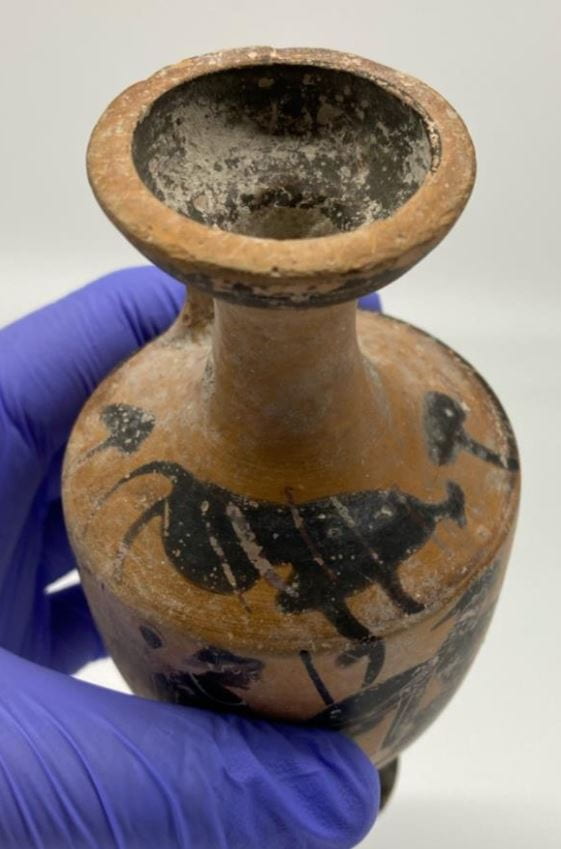

Barsotti’s project focuses on an ancient Greek painted lekythos dating to the early 5th century B.C. It details the current condition of the ceramic vessel and provides conservation recommendations. Here are few of them:

- X-ray image the vessel to search for any evidence of previous conservation

- Soak the vessel in a warm bath of deionized water. Barsotti suspects salts could be trapped in it, which cause cracking paint and general instability. The bath would help dissolve any salts.

- Utilize an acrylic-based adhesive for various repairs on the vessel. She explains that “acrylic based adhesives are important in conservation as they are always reversible.”

These recommendations are not focused on restoring the vessel to its original state. Instead, Barsotti explains the primary goals of conservators today: “Until around the 1970’s, restoration sought to give the illusion of a complete object, while conservators today are not seeking to deceive the viewer into believing there are no broken pieces, but that they be less noticeable and the object can be seen as a whole.”

Reproducing Pottery of the Past

Brynne Moore

Rather than focusing on the needs of an object today, Moore turns her attention back hundreds and hundreds of years ago to processes of original object production. The project compares a 4th century Attic black-figure kylix from the Museum with three black gloss vessels – an aryballos, a stemmed dish, and a ribbed mug – held in other collections.

Moore did not simply examine the original ceramics, however. She took a hands-on approach, reproducing them using two different production techniques and styles. The crux of her argument was “to communicate that there was more than one way to produce pottery and more than one type of artisan (not just the painters) working on the pots in ancient Greek society – even though the traditional view in scholarship is to place most emphasis on the decorative scenes on the vessels and their painters.”

The paper takes readers through the production process, from sourcing clay to shaping the vessel on a potter’s wheel to firing in a kiln. Along the way, Moore explains the constraints she faced reproducing ancient techniques in the modern day.

(She/Her/Hers): The Women of Ancient Greece

Kate Hodgson

Shifting focus from object production to object meaning, Hodgson’s project resulted in an online exhibition examining the “daily lives and notions of gender identity for women from across the Greek world.”

Hodgson selected five Greek objects from the Museum’s collections, spanning from the Early Cycladic Period to the High Classical Period. They range from figurines to loom weights to jewelry and cosmetic containers.

The exhibition highlights each object chronologically, as well as thematically through topics still relevant in the modern world today. Hodgson explores spirituality through a Cycladic idol figurine from Greece and “one of the collections earliest examples of female representation in the cultural production from the Mediterranean.” A Tanagra figurine from Tarentum, Italy opens discussion into identity as these commonly produced figurines “reflect a critical departure in the production of terracotta figurines away from divine subject matter to a new muse – the mortal woman.”

Hogdson also explores the more practical side of life. Women’s roles in the weaving and textile industry are highlighted through a loom weight from Gela, Sicily. Finally, Hodgson shares a Pyxis (pictured) and a marble bust of the goddess Hygeia to discuss beauty and health.

Museum staff were happy to provide access to the collection and appreciate their willingness to share these projects on the Museum’s blog as Campus Community Contributors!