With great diversity comes great responsibility: what we can do to better archive the rich biodiversity of Arkansas

Contributor: Zach Zbinden is a PhD candidate at the University of Arkansas working alongside Drs. Michael and Marlis Douglas. Zach studies fish diversity across the Ozarks using the power of genomics.

Arkansas is hotspot of global freshwater fish diversity, and while many Arkansans appreciate various “sport fish”, most are unaware of the hundreds of other fish species that inhabit lakes, rivers, and streams across the state. Despite our great diversity, we still know relatively little about most of our species, and while museums play an important part in this work, the museum at the University of Arkansas could have a more representative collection of specimens from the Natural State. Therefore, we must work to grow the University collection to better archive and facilitate the study of Arkansas fish diversity for future generations.

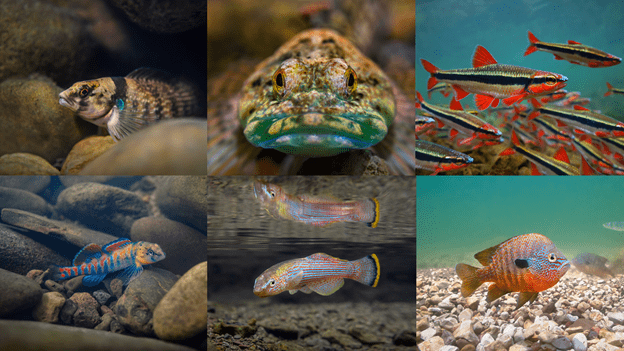

Fig. 1 Rainbow darters found commonly in Ozark streams. Used with permission from photographer, Isaac Szabo (isaacszabo.com).

Arkansas is a fish diversity hotspot

Just north of the University of Arkansas off State Highway 112, there is a small spring-fed creek. During hot summer days, this creek is crowded with locals who are eager to cool off in the crystal-clear waters. Those who look closely will probably notice many tiny fish darting about in the current or along the rocky bottom, or perhaps they may spot a large bass hiding beneath an undercut bank. What few of these folks realize is that just a small stretch of Ozark stream like this one can easily be home to 25 or more species of fish. In fact, the Natural State is part of a major hotspot of global freshwater fish biodiversity.

In total, North America is home to more than a thousand freshwater fish species. More than half of that diversity is found in the southeastern US,1 a region that has been nicknamed the “piscine rainforest” because it is far enough south to remain habitable during periods of glaciation, and far enough north to be safe from flooding during periods of sea-level rise.2,3

Fig. 2 Heat maps of freshwater fish diversity across the United States3 (warmer color = higher diversity). The map on the left shows the total number of fish species by region, while the map on the right shows the number of fish species that are unique, or “endemic”, to each region.4

Arkansas has at least 219 native and about 243 total freshwater fish species.5 Although less than some of the states in the middle of the piscine rainforest east of the Mississippi River, such as Tennessee (301), Alabama (295), and Georgia (265), Arkansas is tied with Missouri for the sixth highest fish diversity by state in the US.5

Fig. 3 Endemic species that occur only in Arkansas: (A) Paleback Darter, (B) Ouachita Madtom, (C) Yellowcheek Darter, (D) Beaded Darter, (E) Strawberry Darter, (F) Ouachita Darter, and (G) Caddo Madtom.

People of Arkansas have a long history of appreciating fish

The first people to live in Arkansas arrived at least 12,000 years ago and were very familiar with regional flora and fauna since they depended directly on nature for their survival. Archaeological evidence suggests fish were a dietary staple for indigenous people of this region, and some even intentionally stocked flooded ponds with fish to grow and harvest.5

The first Europeans to explore Arkansas were Spanish Conquistadors around 1541. They established contact with tribes in the region and recorded numerous accounts of indigenous people catching fish, including catfish weighing over 150 pounds!5 Following the purchase of the Louisiana Territory in 1803, many more people began settling the area and seeing the Natural State — and its immense regional biodiversity — for the first time.

The first systematic study of Arkansas fishes occurred during railroad surveys conducted by the US Army in the late 1800s. As part of these surveys, regional fish specimens were collected and sent to the Smithsonian Institution where they could be studied by two prominent fish biologists, or ichthyologists: Charles Frederic Girard and Spencer Fullerton Baird.5 Many of these specimens were of new fish species that had not been previously described anywhere else in the world, which led these and other ichthyologists of the 19th and 20th centuries to study the fish of Arkansas.

Fig. 4 Notable and historic ichthyologists who studied fishes of Arkansas. From left to right: David Starr Jordan (1851-1931), Seth Eugene Meek (1859-1914), and Carl Leavitt Hubbs (1894-1979).

Why care about fish?

Fish are big business in Arkansas. Over $400 million is spent each year by residents and tourists on recreational fishing supplies, such as fishing licenses and gear. In addition, commercial bait fish production garners more than $20 million annually; and farm-raised catfish and trout bring in around $13 million and $74 million annually, respectively.5

Fig. 5 Two people fly fishing on the Buffalo National River, Arkansas. Photo Credit: National Park Service.

While the economic importance of our regional fishery is undeniable, most fish species in Arkansas have no quantifiable economic value. This does not mean that these species are valueless—quite the opposite. Each species is a vital component of local ecosystems, and has intellectual value for humans.6 This intellectual value stems from the fact that each species is representative of a unique evolutionary lineage with its own history and set of characteristics forged over long periods of time. If examined by an appreciative eye, these unique lineages can provide a wealth of knowledge and insight about different types of fish and the ecosystems in which they reside.6 For example, we now know certain fish species are indicators of either a healthy or declining ecosystem.

Unfortunately, we still do not know the basic biology of many of these fish species, such as which species they interact with, what they eat, or where they live.7 For some of these species, we are desperately running out of time to document their basic biology. For example, there are 50 fish species of conservation concern in Arkansas which includes 4 endangered species. While the extinction of any species is a tragic event, failing to understand the basic biology and intellectual value of species before their extinction adds insult to injury. One tried and true way to preserve the basic biology and intellectual value of species, whether they thrive or become extinct, are regional museums such as the University of Arkansas Museum.

Fig. 6 Arkansas native fishes including (clockwise from upper left): Yolk Darter, Knobfin Sculpin, Duskystripe Shiners, Longear Sunfish, Northern Studfish, Orangethroat Darter. Used with permission from the photographer, Isaac Szabo (isaacszabo.com).

Fish collection at University of Arkansas

Some people may imagine that a museum’s ichthyology collection is an assortment of dusty shelves lined with glass jars of dead fish that are rarely used after their acquisition. In reality, highly trained folks curate and care for the collection to ensure its properly protected and maintained for future generations of students and researchers. For example, each individual jar of fish (known as a “lot”) is carefully tagged with identifying information and catalogued into a digital database, so that students and researchers alike can use the information for both scientific and educational purposes. In most cases, each lot contains several individuals of one species collected at one place at one time, which provides information about particular populations, or groups of interbreeding individuals for a particular species.

The Ichthyology Collection at the University of Arkansas Museum has thousands of fish collected from across Arkansas and the world. This includes an impressive collection of marine specimens, especially for a landlocked state. The collection has been a great teaching aid for generations of biology students. Furthermore, the collection has potential to be used for research into various fields including conservation, environmental health, ecology, and evolution. Perhaps one of the best ways this collection could be used is for community outreach. Let’s face it, fish are cool and can resonate with people. Natural history collections like these can fascinate folks of all ages and help make them appreciate how precious our species and ecosystems are.

Nonetheless, like any collection ours at the U of A could use some improvement to make it even more valuable to our community. For example, the current collection does not include specimens of many fish species that inhabit the state. Actually, the most comprehensive collection of Arkansas fish were not even in the state until the collections of Dr. Neil Douglas from the University of Louisiana, Monroe were moved to Arkansas State University.5 The second largest collection of Arkansas fish biodiversity is still located out-of-state, at Tulane University in New Orleans.5 Interestingly, a large portion of Tulane’s collection was housed, albeit uncatalogued, at the University of Arkansas Museum until Dr. Royal Suttkus salvaged and archived these specimens at Tulane.5

Fig. 7 The fish collection at the University of Arkansas Museum circa 2020. Photos taken by Laurel Lamb.

Today, the Ichthyology Collection at the University of Arkansas Museum consists of about 5,000 lots and about 152,000 individual fish specimens collected in Arkansas. For a geographically proximate comparison, the Sam Nobel Museum of Natural History at the University of Oklahoma has over 56,000 lots and 2 million specimens of fish, and the Royal D. Suttkus Collection at Tulane University has over 200,000 lots and 7 million specimens of fish.

Although the abundance of the specimens in a collection is an important consideration for many research purposes, the variety of species that were acquired over space and time is another critical resource, especially for addressing research questions. The Ichthyology Collection at University of Arkansas Museum has at least one specimen from 160 different fish species collected in Arkansas, or about 66% of the total fish diversity in the state. About half of these specimens were either collected prior to the early 1960s or during the 1990s. Unfortunately, very few contributions have been made over the last 20 years.

Many of these fish specimens were collected by undergraduate and graduate students taking ichthyology courses at the university. In turn, the collection is spatially biased because the vast majority of specimens were collected near and around the university. More than 76% of the specimens were acquired from just six counties: Benton, Crawford, Madison, Montgomery, Newton, and Washington. All these counties except for Montgomery are in Northwest Arkansas. It has been noted elsewhere that study of the fishes of Arkansas has been biased towards the upland streams of Arkansas in the Ozarks and Ouachitas, in part, because numerous endemic species inhabit these isolated mountain ranges that abut the eastern edge of the Great Plains. The lure of these unique species has unfortunately resulted in relatively little attention toward fishes that inhabit the Gulf Coastal Plain, which covers most of the southeastern portion of Arkansas.5

We must grow the collection

Museums are vital for preserving the intellectual value of species for future generations. Biological collections at museums provide an archive of biodiversity from the past, which can tell us how diversity is changing and even allow us to study species that are no longer living today. The specimens in these collections are valuable learning tools for classes such as vertebrate anatomy, evolution, fish biology, and stream ecology. In addition, scientists around the world may access these specimens to address questions related to fish at a regional, continental, or even global scale. Considering the wide range of benefits biological collections provide, what can we do to preserve the remarkable and breathtaking diversity of life in Arkansas?

Ultimately, we need to grow the capacity of our museum through engagement, outreach, funding, and support. Put simply, we need to promote awareness of the awesome collection we have! This will allow for all the various collections in the museum to be seen, appreciated, and acknowledged for their value. Through fundraising and grant opportunities, the museum may allow for professors from various departments on campus to curate different sections of the museum. For example, a curator of fishes or mammals through the Department of Biological Sciences or a curator of rocks and minerals through the Department of Geosciences.

If you are a scientist, we encourage you to use the collection, and advertise it to your colleagues! Specimens here can be studied to test any number of hypotheses that might interest you. Whether you are interested in how characteristics of a species have changed over time or how the composition of communities has shifted in local streams, the collections here can be valuable for your research. And, if you make fish collections, consider archiving them here at your local museum! Be sure to include pertinent information, such as when and where you acquired each specimen.

If you are a teacher, we encourage you to use the collection as a learning tool for your classes. The collection is an excellent way to give students hands on experience with observing biodiversity. Whether you want to highlight differences in morphology and anatomy among species, demonstrate how to use dichotomous keys to identify species, or discuss how characteristics can be used to understand evolutionary relationships, the fish collection is an invaluable teaching resource.

If you are a student and want to get involved, consider taking advantage of one of several opportunities through the museum. The collections are always looking for folks who would like to volunteer to lend a hand with tasks like designing exhibitions. Keep an eye out for job openings with us that can help you get through school while also contributing to the museum! Finally, think about joining the Museum Advisory Council, which is a great way to get involved in a manner that fits your interests and talents like fundraising, events, outreach, and collections. With your help, the council can work to grow the museum and its capacity to archive biodiversity.

If you are an interested citizen and want to help the museum build its capacity to archive any facet of our history and culture, consider becoming a friend of the museum and making a donation! Or if you want to be even more involved, the museum frequently has volunteer opportunities available to anyone here.

Regardless of who you are, next time you happen to be near a body of water in Arkansas, take a second to appreciate the amazing diversity swimming just beneath the surface. I hope you will agree it is important to conserve and archive that biodiversity for future generations to appreciate.

Literature Cited

- Ross ST, Matthews WJ. Evolution and Ecology of North American Freshwater Fish Assemblages. In: Warren ML, Burr BM, eds. Freshwater Fishes of North America 1. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014: 1-49.

- Warren ML, Burr BM. Status of freshwater fishes of the United States: overview of an imperiled fauna. Fisheries. 1994; 19(1): 6-18.

- Robison HW. Zoogeographic Implications of the Mississippi River Basin. In: Hocutt CH, and Wile EO, eds. The Zoogeography of North American Freshwater Fishes. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1986: 267-285.

- Jenkins, C.N., et al. US protected lands mismatch biodiversity priorities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015; 112(16): 5081-5086.

- Robison HW, Buchanan TM. Fishes of Arkansas. 2nd Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Pres; 2020.

- McCord EL. The Value of Species. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2012.

- Matthews WJ. ASIH Presidential Address. 2015; 103: 495-501.